100 Years Ago, Cecilia Payne Discovered What Stars Are Made Of and Revolutionized the Way We View the Universe.

Discover the story of this astronomy pioneer who, in 1925, stood up to a male-dominated scientific community to break the paradigm of her time.

A starry night sky is a cradle of stories, poetry, literature, and science. Since ancient times, the stars have guided humanity, helping our ancestors to navigate the seas, explore new territories, plant and harvest the land, and no less importantly, inspiring myths and legends that founded our civilizations.

Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, a British-American astronomer and astrophysicist, was just 25 years old when she dared to confront a conservative and sexist scientific community, presenting a thesis on the composition of stars that changed the way we look at the universe.

This year we celebrate the centennial of her discovery, and the best way to honor this important date in Astronomy is to learn more about Cecilia Payne’s journey and how she shaped research about the universe.

A Solar Eclipse Leads Cecilia to the Stars

In 1919, Cecilia Payne won a merit scholarship to study botany, physics, and chemistry at Newnham College, University of Cambridge. But a lecture by British astrophysicist Arthur Eddington about the solar eclipse of May 29 that same year would forever change her scientific path.

She would complete her studies in Astronomy but did not receive a diploma, as Cambridge did not recognize this degree for women until 1948.

Cecilia Payne then set off for the United States in search of better opportunities and joined the Harvard College Observatory in 1923 through a program created specifically to encourage women to study at the observatory.

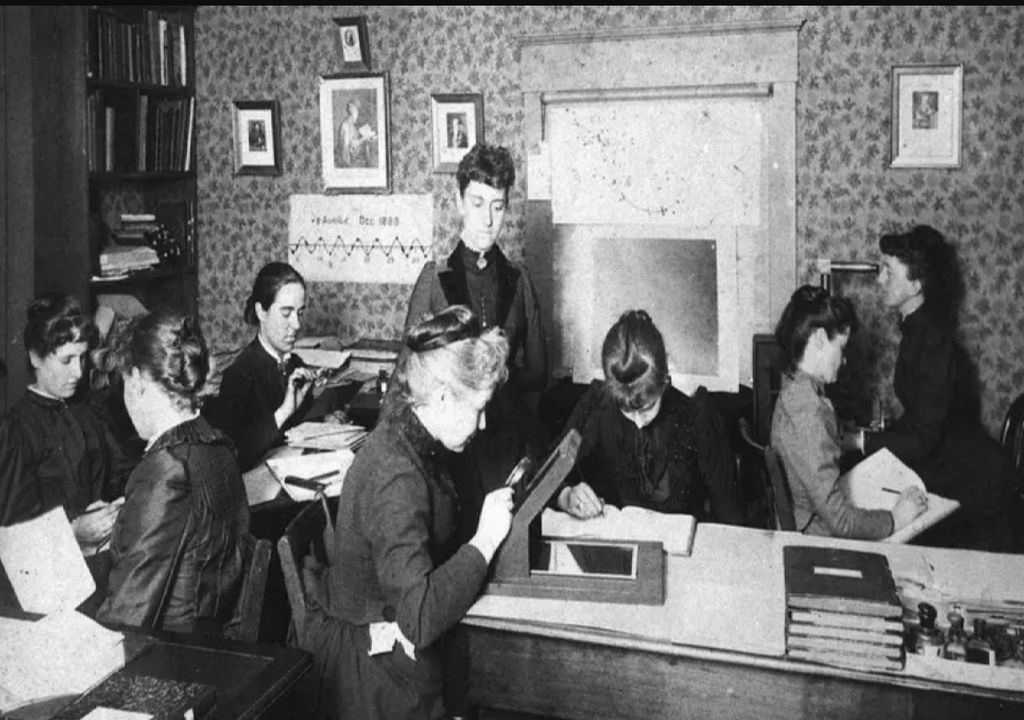

Between 1885 and 1927, the Harvard College Observatory employed around 80 women who studied star photographs made on glass plates. They were known as the "Harvard computers" and made numerous discoveries in Astronomy, such as galaxies, nebulae, and new methods for measuring distances in space.

A Revolutionary But Ridiculed Theory

Cecilia Payne used her knowledge of quantum physics to study the composition of stars. Harlow Shapley, director of the Harvard Observatory, was astonished by her findings and encouraged her to present them as a doctoral thesis.

In 1925, Cecilia Payne presented her revolutionary theory in a dissertation titled "Stellar Atmospheres, a Contribution to the Observational Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars."

Payne applied Indian astrophysicist Meghnad Saha's ionization theory to relate the stellar classification of stars to their absolute temperatures.

Her work was also supported by the cataloging carried out by her colleague Annie Jump Cannon of thousands of stellar spectra, which allowed her to obtain information on temperature, luminosity, and chemical composition of stars.

Helium—and especially hydrogen—are the main components of stars, she argued, concluding that hydrogen is the most abundant chemical element in the universe.

Her thesis contradicted the beliefs of the time, which assumed the chemical composition of stars was similar to that of Earth. Cecilia Payne’s theory was quickly challenged and even ridiculed.

Henry Norris Russell, a highly respected astronomer at Princeton University at the time, dissuaded her from defending her thesis, convinced it was pure fantasy.

Payne was not discouraged, but had to wait until 1929 for her work to finally be validated by the scientific community. Henry Norris Russell himself would reach the same conclusion in his later studies.

A Long Road to Recognition

Cecilia Payne continued her research at Harvard, studying high-luminosity stars to understand the structure of the Milky Way and the Magellanic Clouds.

In 1943, she became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, teaching various subjects at Harvard. However, only from 1945 onward did her courses appear in the university catalogs.

Astrophysicist Donald Menzel took over the observatory in 1954, and two years later, finally promoted Cecilia Payne to full professor at Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences.

In 1956, she became the first woman to be appointed a full professor at Harvard, and her chair was the first occupied by a woman in her department.

Three years before her death on December 7, 1979, Payne received an award for her discovery of the composition of stars, presented by Henry Norris Russell, who had once dismissed her conclusions as “highly unviable.”

Cecilia Payne’s doctoral thesis, presented in 1925, is now considered a milestone in the history of Astronomy. Her findings helped researchers understand what happens on a star’s surface throughout its life—specifically how the energy produced in the core travels to its outer layers and how stars die in explosive events rather than fading away in a dark, mysterious void.

Today, there is consensus among scientists that the study of stars is at the core of astronomical research. All the knowledge we currently have about the universe, in fact, begins with the stars. And that’s why Cecilia Payne’s discoveries were crucial to the advancement of space science.

News Reference:

Owen Gingrich. “The Most Brilliant Ph.D Thesis Ever Written in Astronomy”. Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

Jean Turner. «Cecilia Helena Payne-Gaposchkin». Contributions of 20th Century Women to Physics. UCLA.

Women Astronomical Computers at the Harvard College Observatory. Harvard University